The pursuit of the contemplative life is something for which a great and sustained effort on the part of the powers of the soul is required,

The pursuit of the contemplative life is something for which a great and sustained effort on the part of the powers of the soul is required,

an effort to rise from earthly to heavenly things,

an effort to keep one’s attention fixed on spiritual things,

an effort to pass beyond and above the sphere of things visible to the eyes of flesh,

an effort finally to hem oneself in, so to speak, in order to gain access to spaces that are broad and open.

There are times indeed when one succeeds, overcoming the opposing obscurity of one’s blindness and catching at least a glimpse, be it ever so fleeting and superficial, of boundless light.

[…] We have a beautiful illustration of all this in the sacred history of the Scriptures where the story is told of Jacob’s encounter with the angel….

Like anyone involved in such a contest, Jacob found his opponent, now stronger, now weaker than himself.

Let us understand the angel of this story as representing the Lord, and Jacob who contended with the angel as representing the soul of the perfect individual who in contemplation has come face to face with God.

This soul, as it exerts every effort to behold God as he is in himself, is like one engaged with another in a contest of strength.

At one moment it prevails so to speak, as it gains access to that boundless light and briefly experiences in mind and heart the sweet savour of the divine presence.

The next moment, however, it succumbs, overcome and drained of its strength by the very sweetness of the taste it has experienced.

The angel, therefore, is, as it were, overcome when in the innermost recesses of the intellect the divine presence is directly experienced and seen.

Here, however, it is to be noted that the angel, when he could not prevail over Jacob, touched the sciatic muscle of Jacob’s hip, so that it forthwith withered and shrank. From that time on Jacob became lame in one leg and walked with a limp.

Thus also does the all-powerful God cause all carnal affections to dry up and wither away in us, once we have come to experience in our mind and hear the knowledge of him as he is in himself.

Previously we walked about on two feet, as it were, when we thought, so it seemed, that we could seek after God while remaining at the same time attached to the world.

But having once come to the knowledge and experience of the sweetness of God, only one of these two feet retains its life and vigour, the other becoming lame and useless.

For it necessarily follows that the stronger we grow in our love for God alone, the weaker becomes our love for the world.

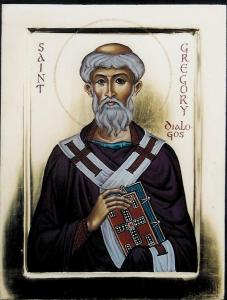

Gregory the Great (c.540-604): Homilies on Ezekiel, 1.12 (PL 76:955) from the Monastic Office of Vigils, Thursday of the Fourth Week of Ordinary Time, Year 2.