Hardships for the sake of the good are loved as the good itself.

Hardships for the sake of the good are loved as the good itself.

Nobody can acquire real renunciation save him that is determined in his mind to bear troubles with pleasure.

Nobody can bear trouble save him that believes that there is something more excellent than bodily consolation which he shall acquire in reward for trouble.

Everyone that has devoted himself to renunciation, will first perceive the love of trouble stir within himself; thereupon the thought of renouncing all worldly things will take shape in him.

Everyone who comes near unto trouble will at first be confirmed in faith; then he will come near unto trouble.

He that renounces worldly things without renouncing the senses, sight and hearing, he prepares twofold trouble for himself and he will find tribulation in a twofold measure.

Or rather: while he refrains from the use of things, he delights in them through the senses; and by the affections which they cause he experiences the same from them that he had to endure in reality before; because the recollection of their customs is not effaced from the mind.

If then imaginary representations existing in the mind alone can torture man, apart from the things corresponding to them in reality, what shall we say when the real things are close at hand?

[…] The hard temptations into which God brings the soul are in accordance with the greatness of His gifts.

If there is a weak soul which is not able to bear a very hard temptation and God deals meekly with it, then know with certainty that, as it is not capable of bearing a hard temptation, so it is not worthy of a large gift.

As great temptations have been withdrawn from it, so large gifts are also withdrawn from it. God never gives a large gift and small temptations.So temptations are to be classed in accordance with gifts.

Thus from the hardships to which you have been subjected you may understand the measure of the greatness which your soul has reached. In accordance with affection is consolation.

What then? Temptation, then gifts ; or gifts and afterwards temptation? Temptation does not come if the soul has not received secretly greatness above its previous rank, as well as the spirit of adoption as sons.

We have a proof of it in the temptation of our Lord and of the Apostles; for they were not allowed to be tempted before they had received the Comforter. Those who partake of good have also to bear temptations.

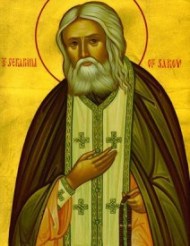

Isaac the Syrian (c. 630-c. 700): Mystic Treatises, 39, in Mystical Treatises of Isaac of Nineveh, trans. A.J. Wensinck (slightly adapted).